All investors wrestle with alpha¹ generation in their investment strategy: What is it worth, in terms of risk or cost, to pursue better-than-average returns? Since active investing is necessary to achieve alpha, what mix of active and passive investing is appropriate given your circumstances?

But there is a question that doesn’t get as much attention in this discussion – how do you maximize performance after taxes? It’s an important question, because many approaches designed to generate excess returns can also trigger taxes. And with federal income-tax rates widely expected to rise at least for higher-income earners, we think now is the time to review these considerations.

ACTIVE VERSUS PASSIVE: A TWO-PART TEST

When working with clients, NEPC starts with a careful consideration of the active/passive decision. Before you can maximize after-tax performance, you have to know where performance can best be found. We use this two-part test to determine whether an allocation to an asset class or region should follow an active or passive strategy:

- We look at the results of active managers within a select universe to evaluate the dispersion of returns. Just as a wide dispersion of stock returns presents greater opportunities for stock pickers to outperform their benchmarks, a wide range of strategy returns also presents greater opportunities for asset allocators.

- We prefer that the median performance of managers in the asset class exceeds the benchmark net of fees. Otherwise, the ratio of outperformers to underperformers can be skewed against investors.

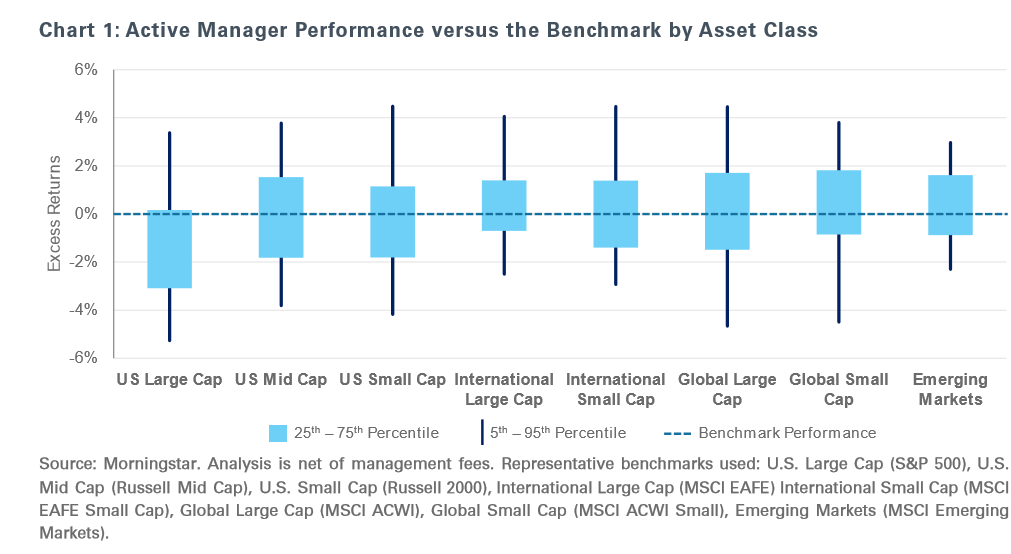

Chart 1 demonstrates that the median active manager performs better in some asset classes than others. It shows the proportion of active managers that were successful in beating their benchmarks over the 10-year period from May 1, 2011 to April 30, 2021. (The light blue boxes represent the 25th – 75th percentile performance, and the vertical dark blue lines show the performance from the 5th – 95th percentile. The dotted line indicates the benchmark’s performance.)

While U.S. large cap, for example, shows a fairly large dispersion of returns, the median performance falls well short of the benchmark. In other words, it passes the first test (albeit the dispersion is negatively skewed), but not the second. As a result, passive strategies may be more appropriate in this asset class. Generally, in more efficient asset classes, outperformance presents a difficult challenge. (An asset class is efficient to the extent that market prices quickly reflect new, publicly available information. U.S. markets, especially in large cap, are highly efficient, given the close attention paid to them by so many investors.)

In the two other U.S. asset classes, dispersion is still relatively large, but the median manager roughly matches the benchmark, representing a more balanced opportunity set.

On the other hand, in some asset classes, the median manager may have better success with outperformance. In international large cap, global small cap and emerging markets, the median managers outperformed their benchmarks by a wide margin even though in some cases the dispersion of returns was narrower. This is not surprising: global markets are much larger and more diverse than U.S. markets and may present managers with more opportunities.

AFTER-TAX PERFORMANCE: PASSIVE VERSUS ACTIVE

Achieving alpha is one thing; keeping alpha is another. Ultimately, after-tax performance is what enables investors to achieve their goals. For us, it’s important to understand whether active strategies that generate excess returns could potentially be generating excess tax obligations as well.

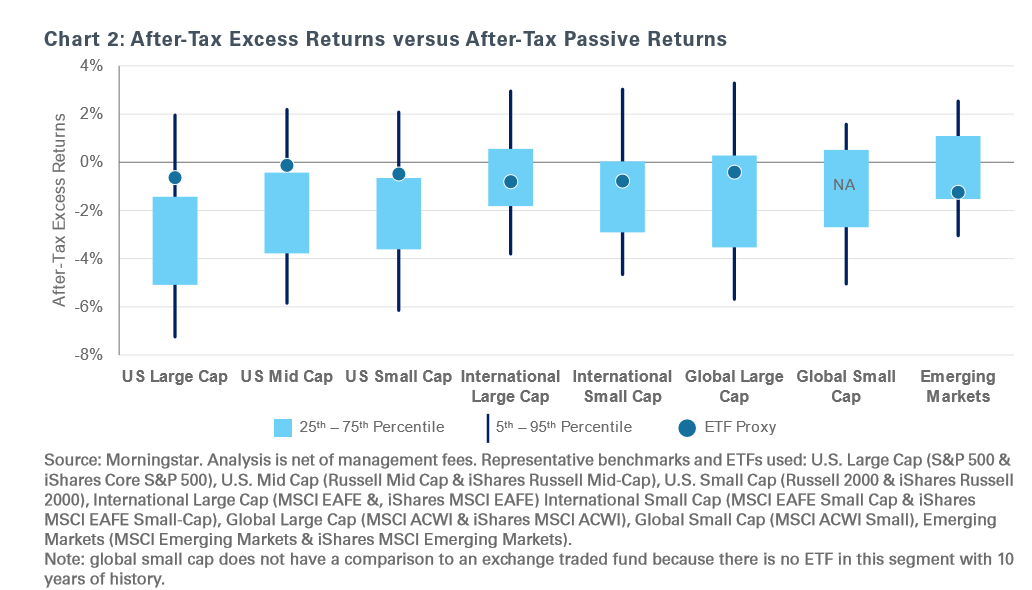

Chart 2 shows after-tax excess returns² of active managers in the same asset classes shown earlier. However, to compare apples to apples, we also plotted after-tax returns for their benchmarks, as indicated by a representative passive ETF. Of course, relative to the pre-tax returns, these after-tax returns are negative.

From an after-tax perspective, a passive approach makes more sense in some asset classes than others. In U.S. large caps, for example, where poor median performance already favors a passive approach, the after-tax performance of the ETF confirms the advantage. The ETF ranks well above the median performance when taxes are factored in; in fact, it ranks in the top 15%.

The advantage of a passive approach is also evident in U.S. mid-cap and U.S. small-cap stocks. Here, even though roughly half of active managers beat the benchmark (as shown in Chart 1), their after-tax performance clearly falls short of the ETF, which exceeds the 25th percentile of active manager performance.

On the other hand, the relatively poor after-tax performance of a passive ETF in some asset classes indicates that an allocation to an active strategy might be more appropriate. In emerging markets, for example, the passive ETF after-tax performance substantially lagged that of the median active manager.

AFTER-TAX ALPHA: AN IMPOSSIBLE DREAM?

Even in asset classes where the after-tax excess returns were relatively high, such as emerging markets, a large portion of them lagged the benchmark during this period. So, what should taxable investors do? Should they give up on achieving outperformance after taxes? We think not.

Part of the problem is that many managers don’t give much thought to taxes in constructing their strategies. After meeting with hundreds of managers, analyzing their portfolios, and monitoring their performance, we have found that those who are tax-aware are in the minority. However, not all managers are alike. As Chart 2 shows, some do beat their benchmarks — even after taxes.

Our manager selection process seeks to add value for clients by looking for those managers we think can achieve excess returns even after taxes by minimizing their impact in various ways. A fund may restrict turnover, for example, to reduce short-term capital gains, which are taxed at higher rates than long-term capital gains. Managers can also make use of tax-loss harvesting — offsetting capital gains with capital losses — that can minimize tax impacts.

CONCLUSION

With the prospect of an increase in federal income tax rates, tax considerations are more important than ever. Investors may want to consider passive strategies for more efficient asset classes and look for tax-aware active managers for others.

Finding managers who operate with tax considerations in mind, however, can be difficult. The effect of taxes is not evident when comparing total returns, and it is typically ignored until tax season. At NEPC, when we evaluate managers, we take on this task, unravelling these complexities for you.

1We use the term “alpha” broadly to refer to any return that exceeds the benchmark. Outperformance or excess returns can be achieved by taking on more risk (or less in a market downturn), while, technically, alpha is outperformance that is achieved while matching the benchmark’s level of risk.

2After-tax returns were calculated by Morningstar.