Sometimes, portfolios are so focused on returns that tax efficiency gets pushed to the back burner. But proposed changes to tax law under the Biden administration—and the related debates—have brought renewed focus to the tax impact of portfolio decisions. That makes now a good time to review some of the key techniques NEPC uses to help manage your investment taxes.

Below is a broad look at a handful of high-value, implementable techniques—some of which may already be at play in your portfolio. Most of these techniques are subject to qualifications or exceptions; your financial or tax advisor can provide more detailed information relating to your situation.

5 Tax-Efficient Investing Strategies

1. Emphasize returns that get the most favorable tax treatment

Most investment portfolios comprise multiple asset types, each with their own return characteristics. Tax law applies different tax rate schedules to different types of returns, with some rates significantly higher than others. Although tax techniques should not override investment decisions, there is always value in assessing the return composition of the assets in a portfolio and, where possible, structuring it so that after-tax return is maximized. Here are a few examples:

Capital Gains vs. Income

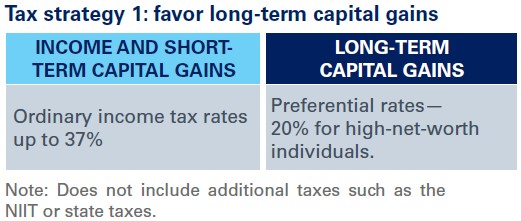

To encourage long-term ownership and greater investment discipline, capital gains on holdings of more than one year are taxed at considerably lower rates than income and short-term capital gains (of less than one year). When it suits a client’s investment goals, strategies that focus on long-term capital gains while reducing short-term gains and ordinary income are far more tax efficient.

There is an additional benefit to capital gains. Since taxes are not paid until the investment is sold and the gain is realized, gains can compound over time, especially in a low-turnover portfolio. This, in combination with preferential tax treatment, can add meaningful value to a long-term investment plan. It should be noted that recent tax discussions have debated changes to this structure; however, at this time, no changes are included in the proposals before Congress.

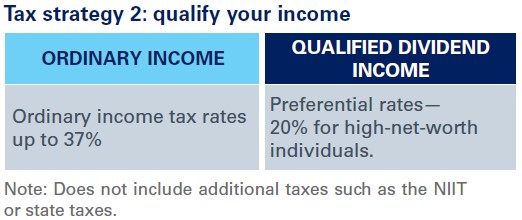

Ordinary Income vs. Qualified Dividend Income

Unlike long-term capital gains, ordinary income is highly tax-inefficient. Income is taxed at the individual’s highest personal rate—typically 37% for a high-net-worth individual. And most high-net-worth clients are also subject to the 3.8% net investment income tax (NIIT), for a total maximum tax rate of 40.8% (and that doesn’t include state tax rates).

But it’s possible to reduce this tax hit by focusing on “qualified” dividend income. Qualified dividends are taxed at the much lower long-term capital gains rates. You may still be subject to the NIIT, but your maximum federal tax rate will be 23.8%, instead of 40.8%.

To be qualified, the dividends must be paid by a U.S. company or a specified non-U.S. firm, and they must not be listed as a type of dividend that is exempt (such as the income from REITs or master limited partnerships). There are also holding period requirements for both common and preferred stocks.

Generally speaking, clients can save significant money on taxes by structuring portfolios to emphasize qualified dividends wherever possible.

Taxable vs. Non-Taxable Fixed Income

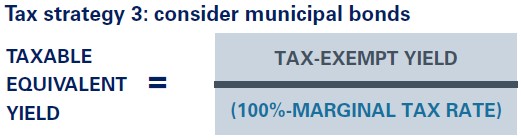

Municipal bonds provide huge tax benefits in a fixed-income portfolio. For the most part, these bonds are exempt from federal taxes, and may be exempt from state taxes as well. As a result, yields on muni bonds are far lower than other types of bonds. But depending on your tax bracket, municipal bond yields often deliver a higher return on an after-tax basis.

When investing in fixed income, it makes sense to compare the yield of municipal bonds to the after-tax yields of taxable bonds. If they compare favorably, they should have a place in your portfolio.

Here’s a quick formula that can be used to determine whether municipal bonds are beneficial for your portfolio. As tax rates increase, the impact of the tax exemption on municipal income increases exponentially.

2. When trading, choose your timing carefully

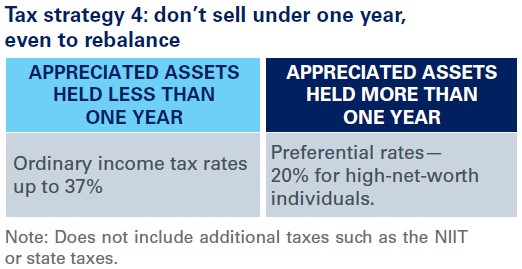

Whenever you make changes to your portfolio, calculate the tax burden that will be incurred upon selling and the incremental added return needed to recoup your original principal. Even if you are simply planning a periodic rebalancing of your portfolio, the tax impact should be taken into consideration. To avoid falling below breakeven, it may make sense to allow allocations to drift further from targets than you otherwise would.

Whenever you make a sale from your portfolio, avoid trimming gains from positions you have held less than a year. As previously mentioned, short-term gains are taxed at ordinary income rates, with the additional possibility of the NIIT. State taxes, particularly in high-tax states, also take a heavy cut. In almost all cases, it’s smarter to look for alternatives to selling short-term holdings. Adjustments can be made in other parts of your portfolio, or you may be able to delay your rebalancing efforts long-enough to allow gains to convert to long-term status.

You can also consider rebalancing using cash flows instead of sales within the existing portfolio. For example, you can invest new monies in positions that will restore your intended asset allocation. You can also direct planned withdrawals be taken from sources that will help generate more portfolio balance.

3. Harvest Your Losses

According to tax law, you are allowed to use capital losses to directly offset capital gains elsewhere in the portfolio (as long as you don’t buy back a similar position within 30 days, called a “wash sale”). This versatile technique, called tax-loss harvesting, requires thoughtful management but is a highly effective way to manage taxes on a large portfolio.

Index portfolios and other passive strategies are typically most efficient when it comes to systematically harvesting tax losses. Active investment managers can use this technique too—and many do—but often only if they feel it does not interfere with their larger investment strategy.

Ideally, you want to capture and use harvested losses as soon as possible. But there are many cases where gains and/or losses should be accelerated or delayed to account for other circumstances. For example, if there are losses from an operating business that could be harvested to offset gains, it may make sense to accelerate gains in the personal portfolio. Timing losses or gains is also a common way to account for expected changes in tax law.

4. Location, Location, Location

From a tax perspective, where you own your securities can be as important as what you own. Most larger portfolios include an array of investments—property, retirement accounts, taxable accounts, and insurance, among others. These entities have unique tax consequences and typically are best suited to certain types of holdings.

An obvious win is owning tax-inefficient investments (such as taxable fixed income or higher turnover strategies) in tax-exempt or tax-deferred accounts. Meanwhile, tax-efficient investments such as municipal bonds and passive equity are better suited to taxable accounts.

Some investment strategies can be especially tax punitive, such as certain high-turnover hedge funds. In these cases, it may make sense to make the investment via a private placement life insurance policy (PPLI), since life insurance proceeds are generally not subject to income tax.

Families with multiple trusts can also take advantage of different treatment for different trust accounts. For example, some families may have trusts domiciled in more than one state; in this case, the allocations in each trust can be tilted to best take advantage of state tax rules. “Defective” trusts can be used to shift the tax burden between family members and beneficiaries as desired. Combining thoughtful asset location with careful estate planning can lead to the most advantageous outcomes.

5. Don’t Sell, Borrow

Instead of selling assets when cash is needed for distributions, capital calls, taxes or spending, you can borrow using the portfolio as collateral. When interest rates are low, it’s worth considering, since the interest cost will likely be lower than the tax cost. But as always, it is important to consider the plan to repay borrowed funds and how it may be impacted by rate increases or estate events.

Nimble Tax Thinking

Many tax-saving investment techniques can be summarized as follows: maximize loss realization—take as much as you can as soon as you can—and defer gain realization—take as little as possible and push out the realization date as far as possible. In fact, one of the best tax-saving devices is to hold on to your winners “forever,” within accounts which will receive a step-up in basis upon an estate event.

But don’t miss the chance to dig deep into the tax implications of your investment strategy when working with your investment advisor or tax advisor. These resources can help you determine what kind of accounts are best suited to various investment strategies. They can also help you evaluate the tax-efficiency of any investment you own.

At the end of the day, your primary investment objective isn’t to minimize taxes—it’s to achieve your larger financial goals. Tax efficiency should never take the place of a smart investment plan, but it can certainly help you achieve your goals more quickly.