Direct investment strategies are becoming increasingly popular with institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals. Direct investments appeal to wealthy individuals and family offices because they not only eliminate the management fees charged by investment firms, but also because the investments can align more closely with the values and mindset of the investor. In this paper we will first focus on trends in direct investing and motivations for private wealth clients. Subsequently, we will examine the performance of direct investments relative to public markets and private fund structures, and then explore strategy development and keys to success.

In the context of a family office, a direct investment represents an investment in a company or asset which is a standalone investment or a co-investment.1 This compares to an indirect investment where the family office is relying on the expertise of an intermediary (commonly known as a general partner) to make an investment in a diversified fund structure, typically charging management and performance fees.

About 67% of high-net-worth-focused practices expect to increase their allocations to direct investments over the next two years, according to a recent study by Cerulli Associates2, underscoring the prevalence of direct investing; this compares to only 22% who plan to increase investments to private equity funds managed by third-parties.

It is worth mentioning that while direct investing is showing an increase in popularity, money into this space has ebbed and flowed for decades; CB INSIGHTS3 notes that corporate venture capital is now in its fourth wave (the four distinct eras are: Conglomerate Venture Capital, 1960 – 1977; Silicon Valley, 1978-1994; Irrational Exuberance, 1995 – 2001; and the Unicorn Era, 2002 to present).

The most obvious motivation for direct investing is to save on the substantial fees paid to intermediaries. Other significant incentives include:

- Concentrating dollars into high-conviction investments

- Capitalizing on family domain expertise

- Career opportunities for the next generation

- Better alignment with family values, i.e., pursuing opportunities with greater emphasis on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors, and socially responsible investments (SRI)

Greater control and transparency over investments - Ability to time entry and exit points for the investment

- Enhanced ability to customize risk exposure

- Avoidance of distractions faced by general partners such as fund raising or dealing with client issues

To be sure, direct investing also has its fair share of detractors who point to the risks associated with family offices investing in individual companies and competing head-to-head against well-resourced general partners and corporations. While venture capital and private equity direct investments can generate high returns, we advise caution and encourage a well-developed strategy to underwrite and monitor these investments and to integrate their allocation with overall client objectives.

Family offices should also be aware of the motivations of institutional investors that are involved in direct investing; in some cases, this could create opportunities for investment as well as competition for deals.

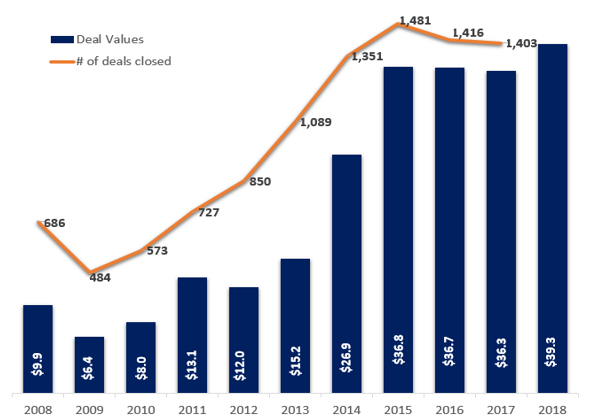

Institutional investors engaged in direct investments include large endowments, healthcare systems and corporations and, like family offices, they have ramped up their efforts. Corporations, as an example, have increased their percentage of venture capital deal value from roughly 27% in 2008 to 45% in 2018.4 Venture capital investments made by corporations (CVC) through the third quarter of 2018 are estimated at $39.3 billion (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Investments by Corporations in Venture Capital

Source: PitchBook-NVCA Venture Monitor (Data as of September 30, 2018)

In addition to enhancing returns, incentives for institutional investors may include:

- Monetization of intellectual property

- Application of new technologies

- Improvement in patient outcomes and experience for healthcare organizations

- Tools to facilitate operating efficiencies and resource management

- Professional growth of employees and ability to recruit talent

Enhanced investment reputation

Potential fee savings are the primary driver of enhanced returns within direct investing. When the typical 2-and-20 private equity fee structure is applied along with other expenses, the total annual cost of these investments is estimated to be 5%-to-7%.5 Theoretically, if a direct investment by a family office underperforms on a relative gross basis, on a net basis it still has the potential to outperform given the magnitude of general partner fees.6

Next, we discuss the performance of direct investments and the lessons learned based on the research in this field.

What Do the Numbers Say?

While the fee savings are appealing, there is little evidence to show that direct investments outperform corresponding private equity fund benchmarks. It is challenging for individual investors to compete with the experience, intellectual capital and deep network of relationships of private equity firms. The performance of direct investments is further diminished when the costs of running such a program are factored in.

Now, we will examine the performance of direct investments relative to both private fund structures and the public markets. The math in favor of direct investments can be compelling: general partners have historically generated gross returns of roughly 18% on buyout funds.7 However, after accounting for fees, net returns earned by limited partners are estimated to be around 11% to 13%, leaving open the prospect of capturing part of the gross and net of fee return differential.

Still, the depth and breadth of skills required to implement a successful direct investing program raises questions around the resources of a family office and the ability to compete with private equity firms for access to talent and deals. To this end, a comprehensive academic study,8 published in 2014, focused on the performance of direct investments from seven large institutions based in North America, Europe and Asia, including universities, corporate and government-affiliated entities.

Specifics regarding the study participants included:

- Average volume of assets under management was $94 billion

- Total alternatives totaled $21 billion

- 15.8% average allocation to private equity

- 390 transactions from 1991 to 2011

- Data on co-investments and solo deals originated and completed by limited partners

The study showed that direct investments usually fall short of beating their private equity counterparts, although the results did fare better than public market indexes with the best performance attributed to buyout funds of the 1990s. The ability to overcome the information advantage held by general partners is an important factor in solo investing.

Results showed that co-investments underperformed the investments in corresponding funds in which they co-invest; this underperformance is attributed to adverse deal selection. The study noted co-investments tend to cluster in the most heated markets and in the largest deals.

Solo transactions outperformed funds; however, both co-investments and solo funds demonstrated performance deterioration over the report’s time horizon, which is an important consideration given the amount of capital waiting to be invested in private companies. The study observed that general partners had less of an information advantage in later-stage investments. The study also noted that direct investments made in firms that were closer in physical proximity to the investor performed better, implying greater involvement in an investment led to better results.

The study also points to the premium that direct investments have earned relative to liquid public equity. However, there are challenges to outperforming general partners and the expertise they bring, even though their fees are substantial. In addition, the benefit of an intermediary—a general partner—is greatest when a unique skill is required, for instance, in the case of venture capital funds, or when there is a premium on access to information. Direct investing in venture capital seems to be particularly challenging given the required domain expertise and the high failure rate of companies in this space.

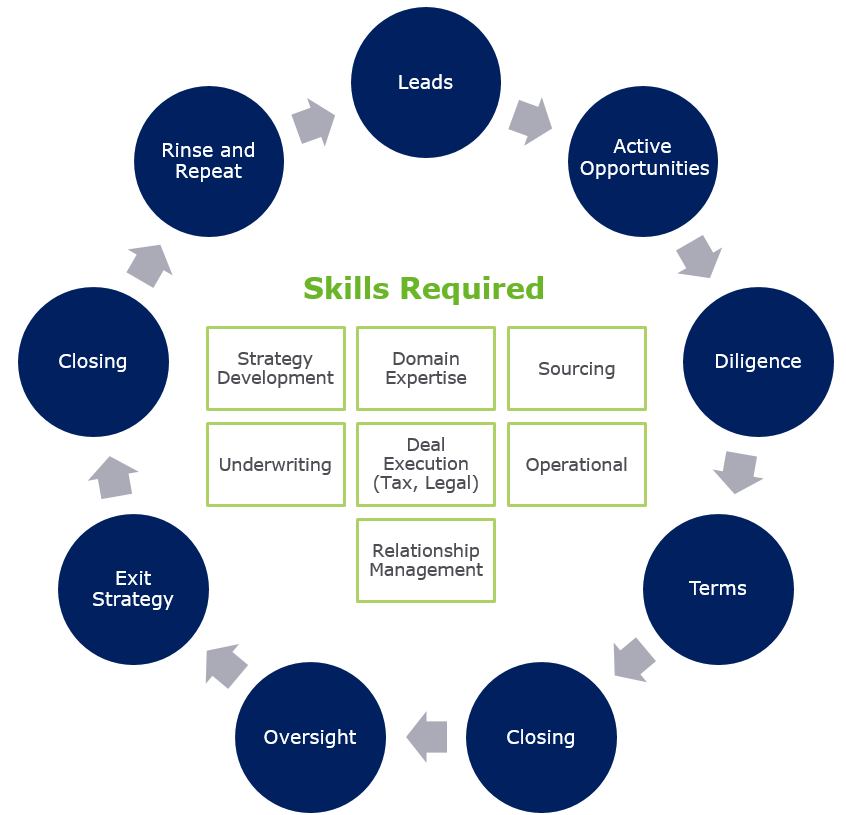

The process of investing in a company is much more complex than selecting a general partner-led investment. It requires a broad set of tasks and skills to make a single direct investment.

Exhibit 2: Direct Investment Cycle and Required Skills

As highlighted in Exhibit 2, there is quite a bit that goes into making direct investments. We will now discuss implementing effective direct investment strategies and keys to success.

Tips for Setting a Program Up for Success

A family office is very likely to be structured differently than a private equity manager, therefore, its approach should differ as well.

When developing a strategy, consider the following:

- Direct versus GP-led fund investments: These should be considered complementary rather than mutually exclusive. Chances are the expertise a family office brings to the investing process does not cover the universe of opportunities; investments in GP-sponsored fund investments can enhance diversification.

- Active versus passive direct investing: Being a board member or an active investor involved in the business will likely provide more control at the expense of a more concentrated portfolio; this may be worthwhile if it aligns with the family office’s investment skill set and organizational structure. Passive direct investments, where involvement is limited once the investment is funded, offer some implementation ease at the expense of loss of control.

- Buyout versus venture capital: The academic study referenced earlier, published in 2014, showed that the likelihood of direct investments falling short of their private equity counterparts is greatest when a unique skill is required, for instance, in the case of venture capital funds when there is a premium on access to information. To this end, buyout-focused investments will likely be a better area for most family offices.

- Co-investments versus standalone: Co-investments seem like a natural first step when developing a direct-investment program. The advantage of co-investing is leveraging the underwriting work of the GP. The challenge is to avoid the potential anti-selection bias and the risks tied to too much capital being allocated to a specific deal or sector. These situations are typically associated with accelerated timelines and the co-investor is usually passive.

- Sector-focused versus generalist: Certain transactions, such as those involving life sciences and technology, require both business acumen and technical expertise, and may be better suited for family offices with a strategic focus and domain expertise. Other industries may be less specialized, and the broad perspective of skilled generalists may provide an adequately strong foundation

- Internally-resourced versus using external resources: Family offices can resource a direct investment internally or utilize third-parties to assist in a variety of functions, including market analysis, valuation support, legal and tax reviews. The key is to have a keen understanding of your own strengths and weaknesses.

- Investing alone versus with others: Investing with others may offer additional insights into the due diligence process and provide the opportunity to share resources and expenses. However, you may need to come to an understanding with your fellow investors on key issues, including the sharing or division of costs and resources, the level of involvement of each party, and how each will deal with success or failure.

For family offices contemplating a direct-investment program, we offer the following suggestions that we believe can help set you up for success:

- Don’t skimp on the due diligence: The nature of direct investments–individual investments in companies compared to an investment in a fund–magnifies the importance of risk management tied to idiosyncratic risks that create the potential for asymmetrical results. If you lack domain expertise or find yourself at a competitive disadvantage, seek the help of skilled third-parties or avoid investments in that space.

- Sound governance: Put systems in place to ensure you avoid chasing deals and that support a thorough due diligence process. These include establishing and monitoring milestones and streamlining decision-making around the potential deployment of additional capital into a company when another round of financing is needed. At the time of the initial investment, it is important to know the capital needed to achieve the exit milestone as not participating in additional rounds of financing could lead to dilution of intended returns.

- Watch out for blind spots: Understand your own bias and weakness, and avoid operating in a vacuum where they can impair the decision-making process. Make sure the size of the investment is appropriate, the organization is equipped to deal with challenges associated with the investments, and the investment program is designed to complement your other portfolio holdings.

1 A Limited Partner’s minority equity investment into a company, which is alongside the lead sponsor’s investment, typically a Fund’s General Partner.

2 ThinkAdvisor. “More HNWs Ditching Private Equity for Direct Investments.” Emily Zulz (February 2018).

3 https://www.cbinsights.com/research/report/corporate-venture-capital-history/

4 3Q 2018 PitchBook NVCA Venture Monitor

5 Gompers and Lerner, 1999; Metrick and Yasuda, 2010

6 https://www.privateequityinternational.com/wanted-by-lps-efficient-fund-management/

7 A Note on Direct Investing in Private Equity. Ludovic Phalippou, Associate Professor of Finance, Said Business School, University of Oxford.

8 The Disintermediation of Financial Markets: Direct Investing in Private Equity. Lily Fang (INSEAD), Victoria Ivashina (Harvard University and NBER), Josh Lerner (Harvard University and NBER) (September 3, 2014).

Additional Resouces:

Touchdown Ventures (http://www. touchdownvc.com/)