There is not a lot of data to call upon to glean the performance of direct private investments; however, based on a large, robust study focused on institutional investors, family offices should know that the performance of this type of investing has been mixed at best.

While direct investments are appealing to wealthy individuals and family offices because they offer the potential to eliminate management fees charged by investment firms, there is little evidence to show that they outperform corresponding private equity fund benchmarks. It is challenging for individual investors to compete with the experience, intellectual capital and deep network of relationships of private equity firms. The performance of direct investments is further diminished when the costs of running such a program are factored in.

In this paper, the second of three, we will examine the performance of direct investments relative to both private fund structures and the public markets. In part one we focused on trends in direct investing and the motivations driving private clients; the final installment will explore strategy development and keys to success.

For a family office, a direct investment represents an investment in a company or asset which is a standalone investment or a co-investment. This compares to an indirect investment where the family office is relying on the expertise of an intermediary—commonly known as a general partner (GP)—to make an investment in a diversified fund structure, typically charging management and performance fees. The math in favor of direct investments can be compelling: general partners have historically generated gross returns of roughly 18% on buyout funds1. However, after accounting for fees, net returns earned by limited partners are estimated to be around 11% to 13%, leaving open the prospect of capturing part of the five-to-seven-percentage-point return differential.

Still, the depth and breadth of skills required to implement a successful direct investing program raises questions around the resources of a family office and the ability to compete with private equity firms for access to talent and deals. To this end, a comprehensive academic study2, published in 2014, focused on the performance of direct investments from seven large institutions based in North America, Europe and Asia, including universities, corporate and government-affiliated entities.

Specifics regarding the study participants included:

- Average volume of assets under management was $94 billion

- Total alternatives totaled $21 billion

- 15.8% average allocation to private equity

- 390 transactions from 1991 to 2011

- Data on co-investments and solo deals originated and completed by limited partners

The study showed that direct investments usually fall short of beating their private equity counterparts, although the results did fare better than public market indexes with the best performance attributed to buyout funds of the 1990s. The ability to overcome the information advantage held by general partners is an important factor in solo investing.

Results showed that co-investments underperformed the investments in corresponding funds in which they co-invest; this underperformance is attributed to adverse deal selection. The study noted co-investments tend to cluster in the most heated markets and in the largest deals.

Solo transactions outperformed funds; however, both co-investments and solo funds demonstrated performance deterioration over the report’s time horizon, which is an important consideration given the amount of capital waiting to be invested in private companies. The study observed that general partners had less of an information advantage in later-stage investments. The study also noted that direct investments made in firms that were closer in physical proximity to the investor performed better, implying greater involvement in an investment led to better results.

The study also points to the premium that direct investments have earned relative to liquid public equity. However, there are challenges to outperforming general partners and the expertise they bring, even though their fees are substantial. In addition, the benefit of an intermediary—a general partner—is greatest when a unique skill is required, for instance, in the case of venture capital funds, or when there is a premium on access to information. Direct investing in venture capital seems to be particularly challenging given the required domain expertise and the high failure rate of companies in this space.

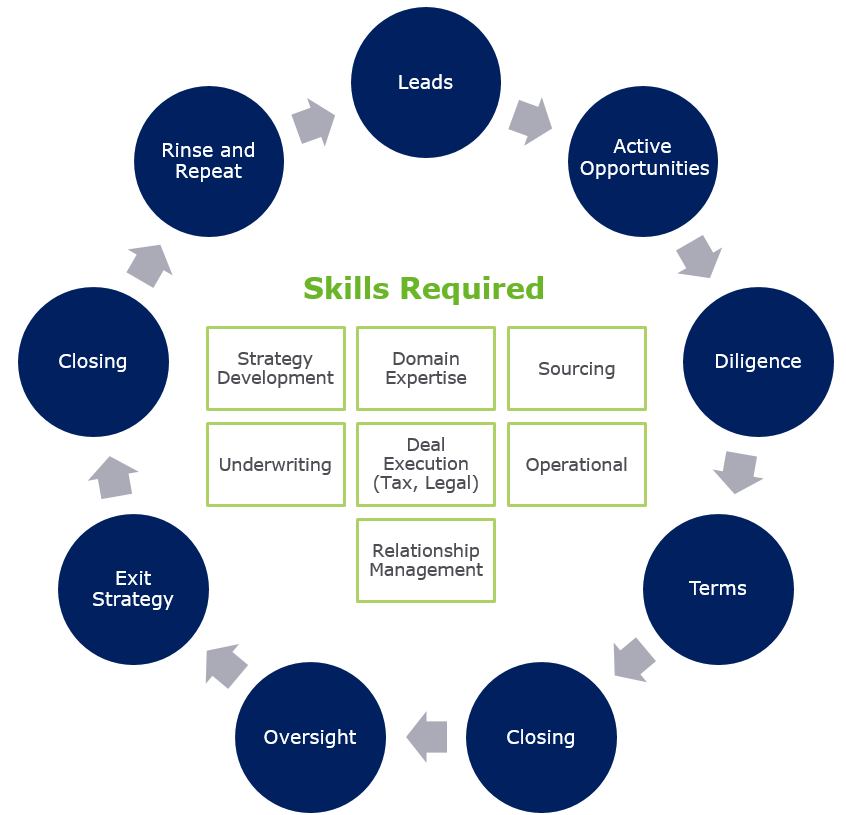

The process of investing in a company is much more complex than selecting a general partner-led investment. It requires a broad set of tasks and skills to make a single direct investment.

Life Cycle of an Individual Investment: Process and Skills

As highlighted in the graphic above, there is quite a bit that goes into making direct investments. In our next paper in May, we will discuss implementing effective direct investment strategies and keys to success.

Additional Sources:

Touchdown Ventures (http://www.touchdownvc.com/)